Introduction

Half of the U.S. population has at least one chronic disease, such as diabetes, chronic lung disease, heart disease, and kidney disease [1]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention identifies these chronic diseases as significant threats to the health status of the country due to their impacts on disability, healthcare costs, and mortality [1]. Chronic diseases become the leading causes of death and disability in the U.S. population, and the total healthcare cost for chronic disease has reached $3.7 trillion a year [1]. The chronic disease prevalence and pattern in the U.S. became more multimorbidity and cross-generational social problems. Populations with chronic diseases are at a higher risk of developing mental health illnesses such as depression and anxiety [2]. Mental health disorders also often co-exist with substance abuse, which contributes to the development of cardiovascular diseases, stroke, cancer, HIV and viral hepatitis, and lung disease [2,3]. A person’s negative health impact from chronic health diseases secondary to mental health and substance abuse comes across to the next generation with long-term effects on a child, associated with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) and developmental problems throughout their lifespan [2,3]. The socioeconomic loss from specialty education, long-term medical management, and productivity loss across the lifespan can aggravate healthcare costs and the disease burden of chronic disease management at multiple social structure levels [4].

The social determinants of health (SDH) - access to care, education, income, food insecurity, job insecurity, and housing- impact more on socially disadvantaged populations [5,6]. Within the social class, race, ethnicity, and income, the underserved populations in the community experience greater health inequity by placing them at a greater risk of developing complex chronic diseases and higher mortality [5,7]. Managing their chronic health condition becomes more deeply woven with multilevel social problems.

Therefore, the management approach should be more comprehensive. However, traditional disease management has significant limitations in responding to complex chronic disease prevalence as it focuses on a linear disease progression and pattern in modern society. The conventional notions in chronic disease management often separate physical problems from behavioral health, and it underestimate the role of SDH’s impact on health. Chronic disease prevention and health promotion, especially for marginalized populations, require a comprehensive and multifaceted approach.

The integrated healthcare model has been introduced into the U.S. healthcare system as a new model in various settings, and global communities have widely adopted its conceptual framework to address the health problems and SDH needs together [3]. This article focuses on the integrated healthcare model implemented in a primary care practice for low-income families in a rural area in Maryland to achieve the highest holistic well-being of the community.

Integrated Healthcare Model

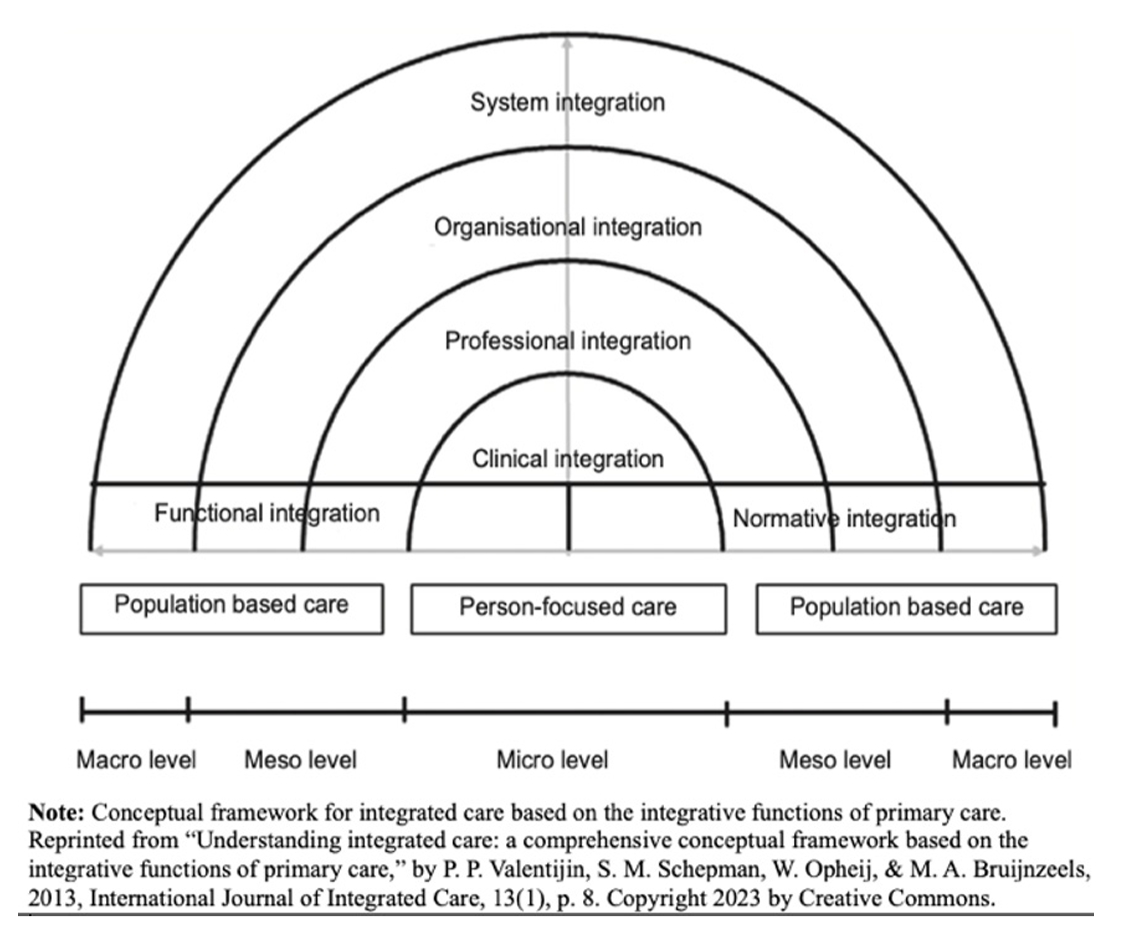

The integrated healthcare model is a comprehensive, person-centered, and interprofessional approach [8]. The integrated healthcare model approaches with a holistic vision focusing on a person’s “personal preferences, needs, and values” rather than focusing on diagnoses or diseases [8]. Its person-centered characteristics make significant changes in socially disadvantaged populations by addressing the person’s unmet needs and promoting empowerment and self-management [8,9]. The integrated healthcare model strategies in primary healthcare aim to prevent and reduce complications of chronic disease, to promote the wellbeing and quality of the patients and their families, to reduce hospital admissions and readmission, and to maximize the capacity of the health workforce [9]. Eight key elements define the fundamental concepts of the integrated healthcare model. The key elements are horizontal (strategies linking services at similar levels), vertical (strategies relating different levels of care), system (rules and policies alignment within the system), organizational (coordination services across other organizations), professional (coordination services across various disciplines), clinical(coordinated care service), functional (coordination of ancillary and support functions), and normative integration (sharing mission and work values within the system) [8]. The multidisciplinary approach through collaboration, open communication, and care coordination connects primary care service with the patient’s health needs at different levels- patients, families, providers, community, and nation [8,10]. Implementing an integrated care model into primary health care shows more cost-effective and satisfactory outcomes for patients and providers and improved chronic disease management outcomes [10,11].

Integrated and Person-Centered Health Home (IPCHH)

Population Description

Carroll County (C.O.) is a rural area in northern Maryland (M.D.). The County’s population consists of Caucasians (90.4%), African Americans (4.4 %), and Hispanics (4.6%) [12]. The C.O.’s overall health outcomes ranked above 75% and is one of the healthiest counties compared to other counties in M.D. However, chronic disease prevalence, emergency room visit rates, and mortality rates secondary to chronic disease have shown significant increases over time[13]. Carroll County’s leading causes of death under age 75 are due to chronic diseases such as malignant neoplasms, heart disease, and chronic respiratory diseases [7]. Mental health illness and substance overdoses, including binge drinking, are identified as rising causes of fatalities and disabilities among the population in C.O., and the suicide rates have been higher than the state average [12,13]. Health disparities between races, ages, and income levels have also played roles in the C.O. population’s health [13]; (1) African Americans lose 800 years more of potential life than Caucasians before age 75 per 100,000 population in C.O. (2) 43.5 % of adolescents have not had routine checkups although more children hold health insurance than adults (3) Adult uninsured rates reached up to 6.2 %, and more than 10% of adults cannot afford the primary care. (4) Access to care challenges become more significant barriers in chronic disease management due to the area’s lack of primary care providers. The primary care provider rates were only 44 providers per 100,000 population, 50 % less than the state average in 2020. (5) The total chronic homelessness has increased by 41%, and youth homelessness also increased by 44 % since 2018.

Health Care and Service Description

Integrated and Person-Centered Health Home (IPCHH) is a non-profit organization providing healthcare services for low-income families in the C.O. The IPCHH is a Joint Commission-accredited and integrated primary care medical home. The organizational mission is “to champion health and provide quality, integrated health care services for low-income residents of Carroll County, Maryland.” [14]. The vision is that (1) “every individual should have access to health care that is coordinated, comprehensive, culturally sensitive, community-based, accountable and high quality,” (2) “all individuals should have the right to health information, the opportunity to participate in their plan of care and the right to accept responsibility for their own care to the extent to which they are able.” [14].

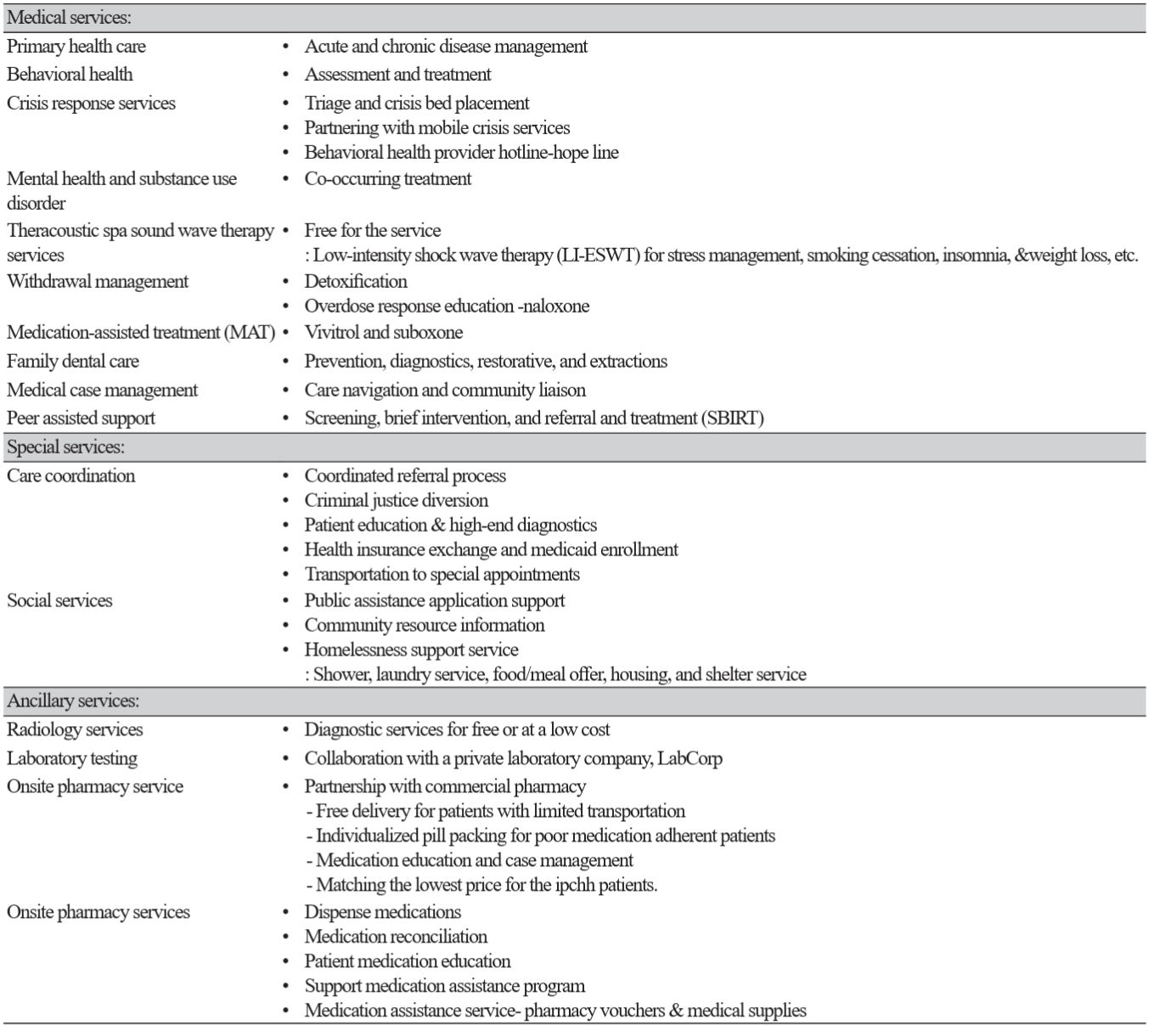

The IPCHH serves diverse populations of all ages in the community- homeless, undocumented immigrants and refugees, veterans, Medicaid / Medicare patients, and prisoners in detention centers. The service fees are based on the person’s income scale, which makes health care available to everyone. The IPCHH provides all health services even if patients do not have money to pay for services at their appointments. The IPCHH provides integrated medical and comprehensive human services to meet patients’ health and social needs. See Table 1. The IPCHH’s medical services include acute and chronic disease management through primary care, mental health services, substance abuse outpatient treatment and counseling programs, and dentistry services. The IPCHH’s patients are screened using validated SDH screening tools at each service entry point. To tackle the identified SDH problems, multidisciplinary teams collaborate to provide the appropriate services through care coordination, referral, and follow-ups. The multidisciplinary team includes organization employees, hybrid staff from volunteers, student internships, health departments, local hospitals, and community partners such as community grassroots agencies.

In the fiscal year 2022, IPCHH provided 6,393 medical services, including 1,072 Detox and substance medication treatments. 6,407 behavioral health services were provided, and 1,256 individuals received peer recovery services. The dental clinic provided 3,207 treatments and diverted 196 ER visits due to dental emergencies. IPCHH also provided 6,761 case management services and managed 456 hospital referrals.

Patient Case Report

A 28-year-old male presented to the clinic complaining of right foot pain and requesting medication refills. He had no primary care provider in the past three years. He learned about IPCHH from the Homeless shelter. His medical history included Type 1 Diabetes since age 14, hypertension, depression, and anxiety. His past medical history was substance abuse with opioids, but he relapsed four weeks ago. He lost his job, insurance, and housing, and he became homeless, staying at the shelter. He had been noncompliant with his Diabetes and HTN treatment plans and did not have care for mental health problems. The electronic record showed multiple E.R. visits for non-urgent medical reasons and repeatedly received medication refills through E.R. care.

During the initial primary care visit, the medical staff interviewed the patient for intake history, including SDH screening and mental health screening questionnaires. The primary care provider (PCP) evaluated identified social problems, mental health, and substance problems while addressing the chief complaint of the visits. The PCP requested a referral to case management, psychiatry consultation, and behavioral health service for substance abuse.

The collaboration and communication occurred dynamically between the multidisciplinary team. The care coordinator, RN, assisted him in applying for federal insurance for low-income persons (Medicaid), food stamps, and medical transportation assistance. The podiatry referral was needed for the diabetic foot ulcer, and the care coordination team scheduled him with a podiatrist in the community who agreed to provide medical services at a lower cost for uninsured patients. The peer recovery team provided brief screening and intervention for his substance abuse problem on the same day. The team provided community resources and made a referral to the outpatient center, but he declined. The patient’s decision was supported, but the peer recovery team continued weekly follow-up with the patient. The team provided the information for all treatment options for substance abuse, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) by IPCHH Psychiatrists, and psychology counseling services were arranged, but there was an 8-week waiting period. The primary care provider bridged antidepressants until the psychiatry appointment, and the patient returned to the office in 2 weeks for the follow-up for his mental health. The IPCHH pharmacy technician and private pharmacy were also part of the care team by reconciling medications and assisting with medical supplies. The IPCHH pharmacy dispensed a glucometer and his insulin for free. He reported the need for dental treatment. He was internally referred to the IPCHH dental clinic. IPCHH performed all the referral follow-ups and SDH and mental health screenings on each visit. Note: Identifying information has been changed to protect patient confidentiality.

Discussion

With the current state of high incidences and prevalence of complex chronic health problems, innovative out-of-the-box solutions are required to tackle the health disparity among the underserved population. An integrated and person-centered healthcare framework is one approach to providing comprehensive healthcare to address health disparities among low-income rural populations [15]. The multidisciplinary services provided through IPCHH primary care show promising continuality of care in response to the evolving population’s health needs and narrowing the health disparities. Therefore, the integrated healthcare model framework may provide a road map for South Korea’s healthcare system to develop strategies to address the evolving health problems in the country related to the aging generation, ethnically and culturally diverse population, and rising substance addiction problems. Future research is needed to evaluate the integrated healthcare model’s effectiveness for the Korean population.